A camp proper is a nomad’s biding place

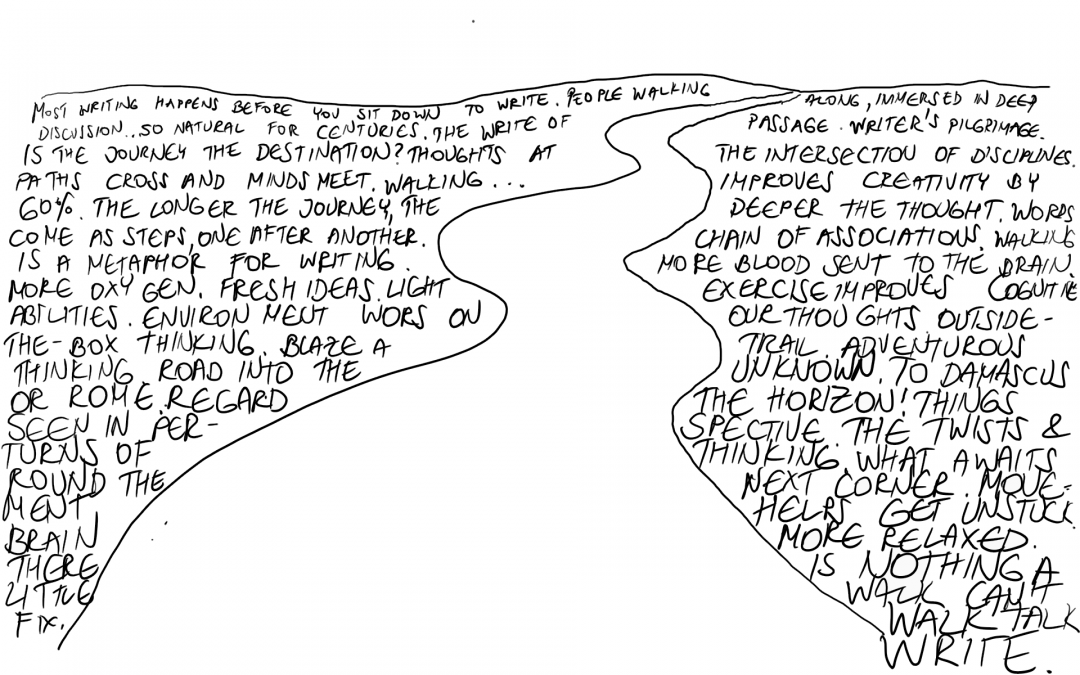

"If you are seeking creative ideas, go out walking. Angels whisper to a man when he goes for a walk." – Raymond Inmon

I present this essay on walking and talking by E Kaye from the Melbourne Bushwalkers in the 1954 no 5 edition of the “Walk” magazine.

We have been walking for a long time, we have been walking for millions of years. We have walked a long way. It took us a long time to walk from the Euphrates Valley to the remotest corner of this world. When the world was young and warm we walked to the Poles; as it cooled we walked back again in the teeth of the advancing avalanche of ice. In Biblical times we walked with Moses to Mt. Sinai. It is even recorded that Enoch walked with God. In classical times we walked with the great philosophers Aristotle and Socrates. In the Middle Ages we walked with the Crusaders, and at Canterbury with Chaucer and the pilgrims. In Dickens’ time we walked with David Copperfield to Dover.

But all the time as we walked we talked.

We talked of the food for which we craved, of the good lands we sought. We philosophised; we told risque stories and sang bawdy songs; but we always talked. Even as we walked the beautiful English Lake district with Wordsworth, we talked. But with Stevenson and Hazlitt we walked alone, our only friend, our thoughts. As I contemplated this I felt sad – I felt that something had been lost. I pondered a long time over Stevenson’s graphic words “The traveller becomes more and more incorporated with the material landscape and open air drunkenness grows upon him with great strides”. I found little to console me in them. It did not deny us the right to talk but it prophesied that as certainly as we grow from children to adults so we should increasingly carry the burden of life alone.

Even as I meditated on this I found one who was not prepared to accept the inevitability of this situation gracefully; one in fact who ruthlessly attacked our right to talk. I quote Sidgwick in his “Walking Essays” who charmingly refers to patrols who “Stride blindly across the country like a herd of animals, reeking little of whence they came or whither they are going, desecrating the face of nature with sophism and influence and authority. At the end of the day what have they profited? Their gross and perishable physical frames may have been refreshed, their less gross and equally perishable minds may have been exercised, but what of their immortal being? It has been starved between the blind swing of the legs below and the fruit Iess flickering of the mind above instead of receiving, through the agency of quiet mind and coordinated body, the gentle nutriment which it is due”.

I could not let this go unchallenged. We are essentially gregarious creatures and our craving for companionship is as primitive as our instinct to walk. Despite all the paraphernalia of this mechanical age we are still merely clothed savages and tend to behave as such. We walk to enjoy life and I submit that we cannot enjoy it alone and in silence. Whilst it is true that good companions, like heroes, are not many, nevertheless, in addition to a handful or perhaps only one special friend, almost all who walk and love nature have a human interest story to tell us.

Our walking clubs comprise people from industry, from commerce, from professions, housewives and students who band together to spend their weekends and holidays enjoying one another’s company. In this fuller world into which they escape for little more than a few brief hours we find many of them bush poets, sages, humorists and philosophers of no mean order. Just as modern society for its strength relies on the integrated efforts of all, so the success of a walk is just as certainly bound up with companionship of one another.

Mr. Sidgwick takes umbrage at us “desecrating the face of nature with sophism, influence and authority”. He says it, I am sure, with his tongue in his cheek. We are there primarily because we love nature, as witness our efforts to preserve what remains of our beautiful heritage in as near as possible to its primitive state. We may have influence and authority, we do not I am sure flaunt it on others. Surely, Mr. Sidgwick, the mere exercise of our minds must do something to ennoble our rather indefinable immortal being, residing as it does rather uneasily between our flickering minds and swinging legs. How much better, surely, to discuss and consider the problems that beset us on our journey through this temporal world. How much better to admit that they exist and to discuss them with one another, rather than skate around them as we did when we were jelly fish. What better place to discuss them than in the setting that we have walked in for so long. For in all the hundreds of thousands of years that we have been walking the advent of the road is a most recent development – a most artificial one.

Mr. Sidgwick wrote mainly of England, and of walks along roads and country lanes, stopping frequently for jugs of ale and other refreshments. Our walking is sterner stuff and even in our own beautiful hills around Melbourne we can spend a weekend walking with seldom a sight of habitation; further afield we must carry food enough for a week or more. It is on these trips a good companion is as indispensable as one’s rucksac or boots. The success of the journey depends not on the miles covered, the mountains climbed nor the prize-winning photos collected. Even the scenery is not the most lasting impression, nor is it really diminished by tired feet or aching back. The paramount and valued gain is the happy memories of the talks on the track and the yarns around campfires. These are the values that the philosophers of other days called the highest good.

I contemplated this a while and felt happier; felt, in fact, Mr. Sidgwick had made his remarks with a smile on his lips, with the solemn intention of provoking something that could be argued about for hours: Whether we should talk as we walk.

This is a quote from one of the walkers in the documentary and is the first time I have heard it.

At times it felt voyeuristic to be watching the raw honesty of these pilgrims as their camino unraveled. The cinematography is beautiful. Core business for the Order. I enjoyed this documentary

You can watch it free on Kanopy if your library subscribes to the service. https://caminodocumentary.org/

Do a keyword search on “the wander society” and your first hit will be the book by Kerri Smith. You will then stumble upon an obscure black and white site. At some point you’ll be watching a vimeo video and for the next few days you’ll be processing what the hell it is you stumbled upon and whether you are a fit.

Suppose it is a construct, and you have been drawn in. It’s no scam. There is no money involved. It feels like a watersmeet of literature and walking which then becomes a confluence of philosophy and spirituality. That talk of a secret society puts you all at sea.

The book is on my reading list and whilst I have not gone there yet, there is a synchronicity in stride with the Order of Walkers.

This essay originally appeared in Eureka Street Volume 9 number 6 by Bill Garner in July/August 1999.

BIll’s book “Born in a tent” was published in October 2013

Whilst it may initially seem incongruous to be associating car camping with walking, both pursuits are linked by the yearning for the simple life. When the vehicle breaks down, we naturally return to the primitive motion.

“For tens of thousands of Australians it is an annual pilgrimage to celebrate a simpler life.”

Bill Garner

For most, this annual pilgrimage will mean packing the car, departing a metropolis at some ungodly hour, arriving at the campsite and parking the car. The vehicle will sit proudly idle for the next week or so. All errands to be run will be walked. A walk will be taken first thing in the morning and then breakfast served with the paper elfresco. A walk to the beach will ensue as the day heats up, and a camping trip (particularly to the beach) would not be complete, without a walk around the campsite or town after dinner to prepare for the perfect night’s sleep.

I commend to you “Gone Camping”

IT IS CURIOUS THAT camping has been overlooked as a significant part of our history. Almost no attention has been paid to it. I am not aware of any histories of camping in Australia. A cursory check of the State Library catalogue reveals directories of camping grounds and catalogs of camping equipment and seasonal articles in the weekend magazines, but no serious studies-not even a coffee-table book.

Yet camping has powerful mythological importance for Australians. It is a relationship to place that spans the settlement divide. Camping has been a common human activity for a very long time. Europeans may have brought tents to Australia but they did not bring camping. The Aborigines are great campers. From their arrival, Europeans found it natural to refer to Aboriginal ‘camps’. The middens along the coast tell us how they moved from one good spot to another, visiting the same sites year after year. And the camper’s eye notes what well-chosen sites they are: near the beach but out of the wind; near a creek but sheltered behind the dunes. Exactly the sort of spots that came to be prized by other campers until they too were driven back from the foreshores by the same conniving partnership of government and land-grabber.

You query the term ‘campers’ to describe Aborigines, fearing that it may be derogatory? Then you are not a camper. Camping is a tradition, indigenous and nonindigenous share without having to anguish about it. It is a love of sitting down on a spot for a while. The Aborigines would arrive at a spot they knew from last year (and the year before that and the year before that), knock up a bark lean-to, light a fire and throw on a feed. Exactly as campers do now with aluminium, canvas and a gas bottle. And, given the chance, we choose-the same sort of spots to pitch our camps. We do this because our parents showed us where and how to do it. The lore of camping is sustained by oral, not written, tradition. Technological innovations cannot hide the fact that the activity itself has not changed over thousands of years. Nomads, gypsies, travellers, campers-we all sustain this living link to the pre-settlement period. Making a temporary camp somewhere, then moving on, still remains the best way to know this or any country.

When anyone landed here they camped. The Buginese camped while they fished for sea slug. The Portuguese and the Dutch camped (but didn’t choose good spots). And when the British arrived they camped too in rows, with flags. Constructed of canvas and rope and wooden poles, these tents were made of the same elements as the sailing ships by which they came. Today, the pitches may have morphed into domes and the rope into synthetic fibre, but tents are still very much with us. We like to have one. How many million tents would there be in Australia? What family does not have one tucked away in the garage or under the house? For there is a handed-down wisdom: we’ll be alright so long as we have a tent. Don’t worry about Y2K: if the worst comes to the worst, we can always camp out.

Explorers carried tents. They were followed by the squatters and settlers whose first dwelling was almost invariably a tent. When gold was discovered, tent cities sprang up. These were our greatest-ever gatherings of campers. S.T. Gill’s drawings illustrate how ubiquitous were the little domestic tents, but there were also tent stores, tent hotels, tent courthouses and tent theatres. It was tent everything. And on the other side of the creek, the Chinese camped in tents too. Even our artists camped. Pictures of tents hang in our national collections. You cannot think visually about Australian history without seeing camps and tents.

When we felt the need to prove ourselves in war we sent campers. We sent campers to the Crimea and campers to the Boer War. And when the big one came in 1914 we created vast canvas encampments at Broadmeadows and then packed them up and took them with us to Egypt. At Heliopolis there were thousands of AIF tents immaculately laid out within sight of the Pyramids. We took tents to Gallipoli. And by God we wished we’d had them at Ypres when the trenches were full of freezing water.

Camping is central to the Australian military experience. Being in the field is called being ‘under canvas’. War is more about camping than about killing. We were still camping in Korea and Vietnam: The heavy-duck, centre-poled, wooden-floored army tent remains about as solid a tent as you can get. You can run up one side and down the other without causing the slightest damage. It’s the brick-veneer of tents. In the housing shortage after the Second World War, people bought them as first homes.

The arrival of the car ushered in the period of the auto-tent. This developed into an annual migration of a large part of the population from suburban villas to the seaside. By the 1950s, camping was the chosen form of holiday-making for most Australians. Campers took over all the most desirable foreshores of the eastern coast. Inland, tents were strung like canvas pearls along the banks of every decent river.

The Golden Years of camping lasted until the late 1960s. This was camping by choice rather than necessity. Although there were designated campgrounds, usually administered by local shires, many people preferred to find a quiet little spot of their own, away from everyone else. You could camp almost anywhere. The law was lax, or rather, relaxed. The beach side of the coastal roads belonged almost exclusively to the campers. You won’t find many tents there now. Only ‘No Camping’ signs.

But Australians are a camping people. It’s in the blood. When I set out as a 22-year old to cross Asia to Europe on the overland trail, I carried a tent (as well as a billy, a frying pan, flour and salt). That was in 1966, not 1866. I carried my house on my back. I slept out. I was self-sufficient. That seems quaint today, but once it guaranteed survival.

Campers pride themselves on getting by with as little as possible. This is not a fashionable attitude. Camping is for getting on the cheap what others pay for. That is heresy in a world that says the best should be reserved for those who can pay the most. And even though it is now possible to support your camp with all sorts of clever gas appliances, the basic experience of camping remains that of doing without. For tens of thousands of Australians it is an annual pilgrimage to celebrate a simpler life.

It goes beyond proving that you can survive without electricity. Camping connects you directly with the earth and the sky, the vegetation, the animals and especially the birds: The strength of the wind; the power of the waves; they overwhelm you. You understand the scale of things and your own place. Camping is a test of endurance. You can’t avoid the elements. ‘Going inside’ a tent is no escape. You have to tough it out. But if you want to know this land, experience it, there is no better way. When you camp you live in the dirt, in the rain, in the sun.

But camping is unfashionable in government circles. It resonates too much with the old values. For above all it is a profoundly egalitarian experience. It is a greater leveller than spectator sport and it remains staunchly amateur. There are no corporate boxes (although they’re working on that). While there are classes among campers, they reflect camping skills and not wealth. The rich do not necessarily have the best gear and those with the best gear are not necessarily good campers. Good campers are those who camp well, using what they have.

In campgrounds everyone is always on view. A popular pastime is walking along the lines looking into other people’s camps and acknowledging particularly elegant or ingenious set-ups. The only fences here are windbreaks made of hessian. This lack of privacy is another thing non-campers find abhorrent. It is also why privatisation is inimical to camping. Camping is a public, communal activity where ‘privacy’ is respected by keeping your radio down, not by hiding your bodily functions. The great gathering place is still the public bath now known as the shower block.

Improvisation is particularly admired by campers. Camping is one of the few activities where skill with a piece of fencing wire, or similar, is still appreciated. If this seems a compendium of old Australian virtues, it is not surprising. Camping sustains the old culture. Camping lore is passed down from hand to hand, generation to generation. Skills and tools are shared. People keep an eye out for one another’s stuff. Children wander freely in next door and are rewarded with a biscuit. Above all, campgrounds exhibit every known form of the extended family, gathered in an atmosphere of kindly tolerance.

And yet for some years simple family camping-this quintessential Australian experience-has been coming under sustained attack. We have been driven back from the beach side of the road. We have been corralled into reservations. They won’t let us have our dogs. Sound familiar? Campers are being pushed away from the coast for the same reasons as were the Aborigines. We are in the way of progress.

We mess up the view. Our primitive encampments ‘greedily’ exclude those who want to enjoy the scenery through picture windows. Quite simply, we have found ourselves in the way of profit.

Camping is becoming an endangered activity. It should be protected. It is important for the culture. But the family camping holiday does not sit comfortably with the tourist industry because camping is about minimising economic activity rather than maximising it. The last thing most campers want is more service. It’s all about doing it yourself-another of these old Australian values.

Now the Victorian Government wants to force the shires to sell off their campgrounds to entrepreneurs who will ‘make better use of them’, meaning that they want to extend upmarket accommodation at the expense of campers. This is a violation of the whole tradition of camping on public land that has been a continuous part of our national culture not only recreationally but also historically and spiritually.

So far this battle has been joined mainly with respect to high-profile places such as Wilson’s Promontory. But for many years campers have been feeling the squeeze all over the state. Privatisation of publicly owned campgrounds is the last stage of this process. The plan has been drawn up. But this is not simply about certain places. There is something else at stake. How is it, that those in power seem to have missed the historical and cultural significance of this simple, inexpensive, inclusive, very Australian activity? Perhaps it is because no-one has put it in these terms. Or perhaps it is because it is so cheap. In dollar land, nothing cheap is valuable.

There is an ideological mote in the government eye that seems to prevent it from seeing the cultural importance of camping. It may be true that there is a relatively small economic advantage to be extracted from it compared with farming tourists. Family camping is essentially a domestic activity. It is not marketable to the international trade. In fact, as at The Prom, it is seen to get in the way of potential business by taking up valuable space. Even more distressing may be the suspicion that campers actually seek to subtract financial value in order to add spiritual value Camping links us both to our ancestors and to the land. It is time to defend it as a major culture form in its own right.

Bill Garner

An item of interest from the University of Auckland. New Zealand

Mats Andren, a practitioner of the Order of Walkers, keeps a careful and thoughtful log of his travels around the world. I commend to you his audio podcast series. He is walking from Stockholm to Sydney.

https://play.acast.com/s/thewalk

In particular I draw your attention to

Five Thoughts on Long Distance Walking | the-walk.se on Acast

This is a question that has been worrying most walkers ever since they first got the idea of going out of doors and spending their leisure time in such an abnormal manner. The walking, mountaineering and camping journals of the world have all published contributions by people trying to do themselves justice by explaining their actions to a doubting world. It is human nature to be interested in the logical justification of one’s actions, especially when, as in the case of bush- walking, the rigors of the game often by no means make for personal comfort.

Many good reasons have been advanced. For some the lure is purely and simply the desire for physical exercise, either for its own sake or for the physical fitness which ensues. There can be no doubt of the sense of well-being invoked by steady exercise taken in the fresh, clear air of the hills. There is also the satisfaction to be derived from the self-reliance essential for a trip in a remote area. Others are attracted by the companionship to be found on the track. No matter what your vocation or station in everyday life, once you join a walking party you get a new start; you are accepted for yourself. The pleasures of camp life away from all reminders of your ordinary existence cannot be under-estimated. Companionable sing-songs around the campfire leave many happy memories, as do days spent just soaking up the sunshine, or maybe paddling around the quiet pools of some mountain stream. The clock, although it still exists, ceases to dominate; where at home seconds are important, in the bush the unit of time can quite easily be the hour, or at worst the half-hour. Then, too, many people praise the charms of the scenery to be found away from the motor roads when one has the leisure provided by travelling per Shank’s pony. Especially in Australia where most of our scenery is not publicised but needs seeking out, does this leisureliness pay dividends of enjoyment. To us is often given the privilege of seeing things that few who do not walk can ever set eyes upon. If ever they should be able to drive over our routes we would know that the very road they travel changes the scene we knew. Finally, there are some who have been accused, often with some justice, of being attracted by the paraphernalia and gadgetry which some manage to introduce into their walking; the desire of the juvenile mind for fancy dress.

Any of the above reasons may be sufficient in some cases, but really most of us respond in part to a synthesis of them all, although there are many who do not waste time thinking about the matter at all; they walk because they enjoy doing so. Let’s all just enjoy it, and maybe in that way we’ll really get the most from our walks. The real enjoyment of a walking trip does not lend itself to logical analysis; in it there is much of the spiritual. Bushwalking demands an act of faith; we must put forth the effort before we can know that there is any reward. Once having made the effort we have no doubts. We just enjoy our walking.