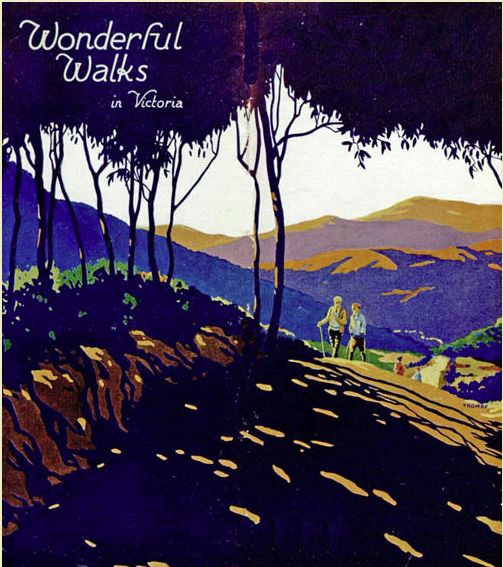

As the car made its way up the tarmac ribbon that runs from Harrietville to the top of Mt Hotham, the setting sun filtered its way through the trees. One of the intrepid hikers aboard took a moment to enjoy the comfort he would leave behind for the next few days. He closed his eyes and smiled, enjoying the dysrhythmic dance of light and shade being performed upon his eyelids.

In time the car climbed above the snowline and disgorged its occupants. They stood on the slopes of the broad mountain looking across the ridge to the north, the left hand side of their faces painted a gentle orange by the hazy orb that hung so low in the sky it seemed beneath them.

The Razorback – the ridge upon which they would be walking was well named as each undulation that rose along it bore an undeniable resemblance to the lumbar joint of a giant. The spine of this sleeping titan stretched far out into the distance, crowned by a steep conical peak ten kilometres away – Mt Feathertop.

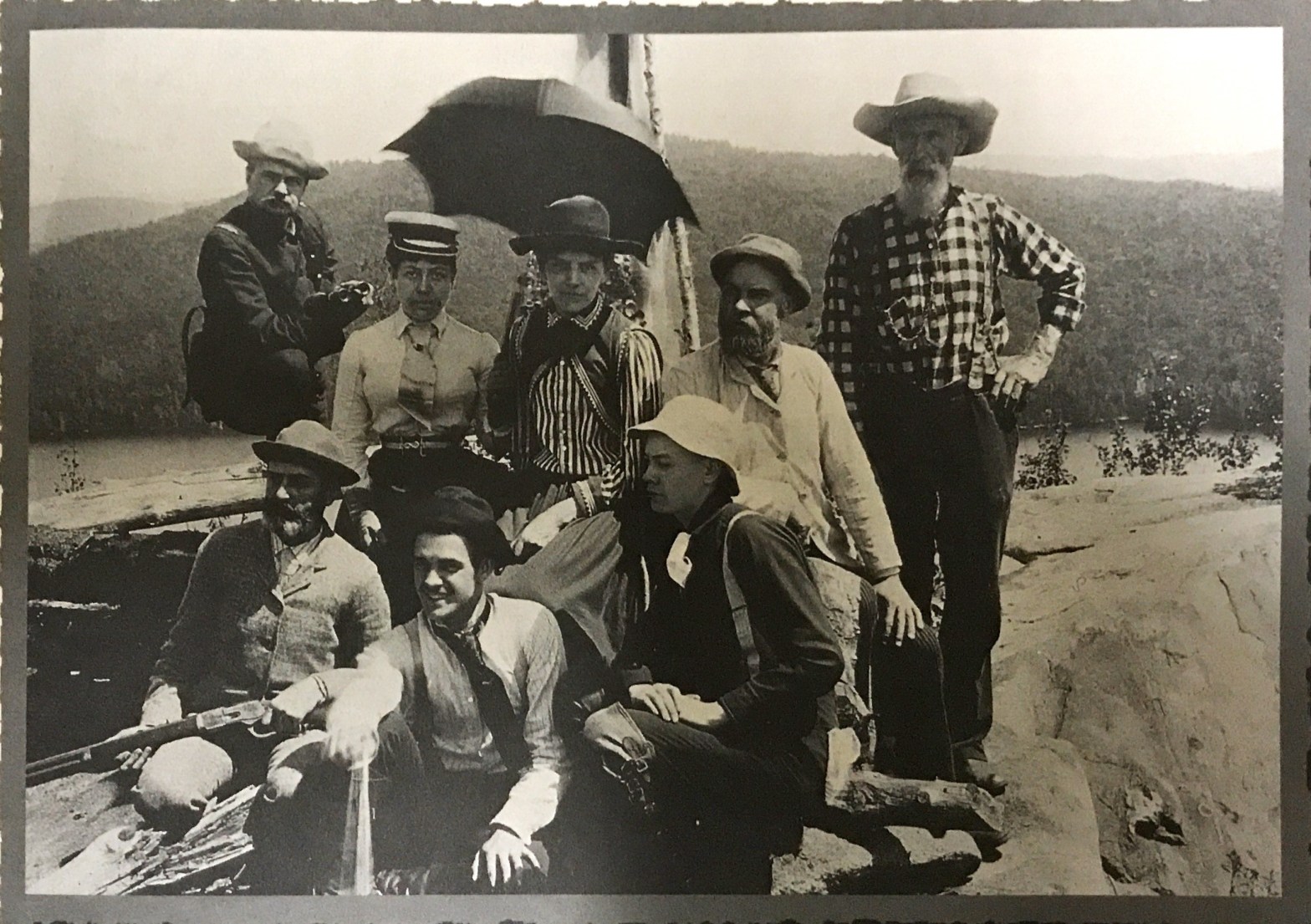

With nary of word said among them, the group of five shouldered their packs and set off down the track that led along the ridge. Such was the ethereal calm that soon fell over the party that conversation seemed an unnecessary ornament to the occasion. In the distance the occasional cry of an unseen bird was all that could be heard beyond the crunching footfall of the five men.

The world – the other world, full of demands and denials became hard to perceive, hidden behind the veil of nature that had been drawn around them. Payrolls and pay rises seemed inconsequential as the soft light of dusk gave way to the clarity of night. To the west the sun fell below the horizon as a hunter’s moon rose in the east. Up the centre of the celestial equilibrium walked the hikers, each man in his own headspace, interpreting the outlook in his own way.

The stars came out so slowly, no-one was sure when they had first appeared. Of course, they had always been there, even in the daytime, staring down dispassionately from the heavens. But they did not seem indifferent to the walkers – they were as benevolent as the maternal moon which lit the way across shards of granite and mounds of loam that lay across the track.

In the cooling alpine air, a faint umbra encircled the moon, a halo upon the head of the walkers’ guide. The line of men stretched out and the distance between the fastest and slowest walker grew to half an hour. And yet despite this space, there was a unity that had enveloped the group. A unity of purpose and of place. They had separated themselves from bricks and steel of the city and were now a part of the sublime architecture of the Australian bush. Although the path ahead could be seen for miles – literally – each step taken uncovered a unique perspective upon the land before them. Subtle changes in mountainscape rewarded their labours: little moonlit dells and wooded enclaves were glimpsed at; an unseen brook played a delicate tune somewhere beyond a copse of thin, dark trees; a line of rocks resembling hunched trolls appeared and disappeared like Celtic spirits. And whilst they walked across this surreal stage, each man’s thoughts gradually turned inward, persuaded there by the peace that lay upon the land. Their ruminations they kept to themselves – it was not their way to share such things – but one thing was clear by the time the last man walked into the campsite below Mt Feathertop – all had found that special peace known to people who venture out into the wilderness. Without articulating it each man had been reminded of the secret that all hikers know – the further one goes out into the natural world, the more he travels towards himself.

Paul Stewart is an educator, writer, walker and talker. He can do some of these things at the same time. Paul spends his working days as Head of Middle School English at Melbourne Grammar School and the rest of his time is spent enjoying friends, family and the world at large.